A planet made of diamond

26 Aug 2011

A once-massive star that’s been transformed into a small planet made of diamond: that is what University of Manchester astronomers think they’ve found in the Milky Way.

The discovery has been made by an international research team, led by Professor Matthew Bailes of Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, and is reported in the journal Science.

The researchers, from The University of Manchester as well as institutions in Australia, Germany, Italy, and the USA, first detected an unusual star called a pulsar using the Parkes radio telescope of the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and followed up their discovery with the Lovell radio telescope, based at Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, and one of the Keck telescopes in Hawaii.

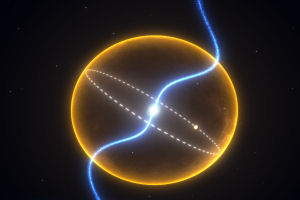

Pulsars are small spinning stars about 20 km in diameter – the size of a small city – that emit a beam of radio waves. As the star spins and the radio beam sweeps repeatedly over Earth, radio telescopes detect a regular pattern of radio pulses.

For the newly discovered pulsar, known as PSR J1719-1438, the astronomers noticed that the arrival times of the pulses were systematically modulated. They concluded that this was due to the gravitational pull of a small companion planet, orbiting the pulsar in a binary system.

The pulsar and its planet are part of the Milky Way’s plane of stars and lie 4,000 light-years away in the constellation of Serpens (the Snake). The system is about an eighth of the way towards the Galactic Centre from the Earth.

The modulations in the radio pulses tell astronomers a number of things about the planet.

First, it orbits the pulsar in just two hours and ten minutes, and the distance between the two objects is 600,000 km—a little less than the radius of our Sun.

Second, the companion must be small, less than 60,000 km (that’s about five times the Earth’s diameter). The planet is so close to the pulsar that, if it were any bigger, it would be ripped apart by the pulsar’s gravity.

But despite its small size, the planet has slightly more mass than Jupiter.

“This high density of the planet provides a clue to its origin”, said Professor Bailes.

The team thinks that the ‘diamond planet’ is all that remains of a once-massive star, most of whose matter was siphoned off towards the pulsar.

Pulsar J1719-1438 is a very fast-spinning pulsar—what’s called a millisecond pulsar. Amazingly, it rotates more than 10,000 times per minute, has a mass of about 1.4 times that of our Sun but is only 20 km in diameter. About 70 per cent of millisecond pulsars have companions of some kind.

Astronomers think it is the companion that, in its star form, transforms an old, dead pulsar into a millisecond pulsar by transferring matter and spinning it up to a very high speed. The result is a fast-spinning millisecond pulsar with a shrunken companion—most often a so-called white dwarf.

“We know of a few other systems, called ultra-compact low-mass X-ray binaries, that are likely to be evolving according to the scenario above and may likely represent the progenitors of a pulsar like J1719-1438” said team member Dr Andrea Possenti, Director at INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Cagliari.

But pulsar J1719-1438 and its companion are so close together that the companion can only be a very stripped-down white dwarf, one that has lost its outer layers and over 99.9 per cent of its original mass.

“This remnant is likely to be largely carbon and oxygen, because a star made of lighter elements like hydrogen and helium would be too big to fit the measured orbiting times,” said Dr Michael Keith (CSIRO), one of the research team members.

The density means that this material is certain to be crystalline: that is, a large part of the star may be similar to a diamond.

“The ultimate fate of the binary is determined by the mass and orbital period of the donor star at the time of mass transfer. The rarity of millisecond pulsars with planet-mass companions means that producing such ‘exotic planets’ is the exception rather than the rule, and requires special circumstances,” said Dr Benjamin Stappers from The University of Manchester.

The team found pulsar J1719-1438 among almost 200,000 Gigabytes of data using special codes on supercomputers at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, The University of Manchester in the UK, and the INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Cagliari, Italy.

The discovery was made during a systematic search for pulsars over the whole sky that also involves the 100 metre Effelsberg radio telescope of the Max-Planck-Institute for Radioastronomy (MPIfR) in Germany. “This is the largest and most sensitive survey of this type ever conducted. We expected to find exciting things, and it is great to see it happening. There is more to come!” said Professor Michael Kramer, Director at the MPIfR.

Professor Matthew Bailes leads the ‘Dynamic Universe’ theme in a new wide-field astronomy initiative, the Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO).

The discovery of the new binary system is of special significance for him and fellow team member Professor Andrew Lyne, from The University of Manchester, who jointly ignited the whole pulsar-planet field in 1991 with what proved to an erroneous claim of the first extra-solar planet. The next year though the first extra-solar planetary system was discovered around the pulsar PSR B1257+12.